The Chili Line

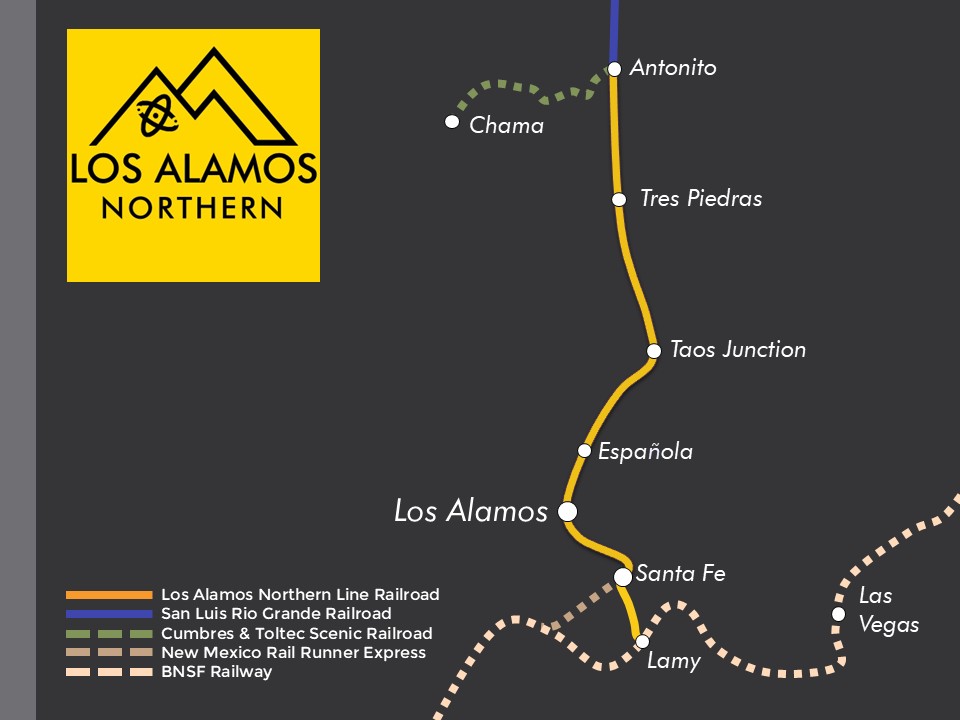

The Chili Line (officially the Santa Fe Branch) was built by the Denver & Rio Grande Railway (later Denver & Rio Grande Western, D&RG / D&RGW) to connect Antonito, Colorado, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. Construction began around 1880, reaching Española, NM first. Then the Texas, Santa Fe & Northern Railroad was incorporated to build the remaining segment from Española to Santa Fe, which opened in 1886 (or 1887 in some accounts) and was transferred to D&RG soon after.

The line was 3-foot narrow gauge, about 125.6 miles in length. Passenger, freight, and mail services were mixed. It carried livestock, lumber, mail, general merchandise, and occasional passengers. Freight was varied, including agricultural goods from the region; legends say chile peppers were among the cargo, which helped give the line its popular nickname, “Chili Line.” In terms of geography and engineering, the line had challenging segments. For example, the climb from Embudo through Comanche Canyon to Barranca had steep grades (around 4%) and twisting alignments. Otherwise, many segments had gentler grades by following river valleys (e.g. the Rio Grande) or plateau edges.

Despite its utility, the line was never especially profitable. Profits were squeezed by geography, maintenance costs, and the difficulty of operating in remote high‐terrain.

By the 1930s, however, declining traffic and growing competition from highways were nearly sealing the line’s fate. Plans for abandonment were well underway when world events intervened. With the outbreak of the Second World War and the establishment of the secretive Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, the federal government sought reliable rail access to the remote mesa. The dormant Chili Line offered the most direct solution.

In 1943, the 125-mile stretch between Antonito, Colorado, and Santa Fe, New Mexico, was converted from narrow to standard gauge, with new alignments created to remove many of the steep grades and twisting alignments, all under government direction. The route was immediately placed under tight security, with new sidings, depots, and interchange facilities constructed to handle classified shipments. Daily local trains continued to operate between Santa Fe and Antonito, while the connection with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe in Santa Fe became a major artery for materials and personnel bound for the Los Alamos Laboratory.

Post War

Following the war, the Chili Line continued to serve as a critical supply line for ongoing research and defense operations in northern New Mexico. Freight diversified through the 1950s and 1960s, ranging from scientific equipment and construction materials to agricultural goods and manufactured products. By the late 20th century, the railroad had modernized much of its infrastructure, maintaining its unique dual role as both a regional carrier and a strategic link to one of the nation’s foremost research institutions.

The Los Alamos Northern Line Railroad

By the turn of the 21st century, the landscape of western railroading was changing. The Denver & Rio Grande Western had long since merged into the Southern Pacific, which itself was soon absorbed by the Union Pacific Railroad. Amid this sweeping consolidation, the rail lines of northern New Mexico faced an uncertain fate.

In 2003, Union Pacific began divesting portions of its lesser used routes, seeking to focus on its mainline operations. From this transition emerged a new name, the Los Alamos Northern Line Railroad, backed by the operations and maintenance division of Sur Rail, the small but determined successor was tasked with preserving service across the historic Chili Line corridor.

Around the same time, a separate transaction gave rise to the San Luis Rio Grande Railroad, which inherited the trackage stretching across the fertile San Luis Valley. Union Pacific believed the valley routes would stand stronger on their own as a separate sale, originally thinking that the Chili line would once again face abandonment.

New Mexico Gold

The Jemez Mountains rise from the heart of northern New Mexico, part of the vast Cenozoic volcanic fields that stretch from east-central Arizona to the high mesas of the Rio Grande Valley. Rich in mineral deposits, the region’s layers of volcanic rock and sediment conceal significant reserves of sediment-hosted and porphyry copper. It is this very geology that paints the landscape in the deep reds and ochres so iconic to the Southwest.

As advances in extraction technology made once-inaccessible ore bodies viable, a new surface mine was established at the eastern base of the Jemez near Los Alamos, the Otowi Mine. A companion mine had also been established on the western base of the Jemez new Zia Pueblo and is served by the Zia Railway. The opening of the Otowi Mine marked a new era for the Los Alamos Northern Line Railroad, which became the mine’s primary artery for outbound copper and inbound supplies.

The surge in mineral traffic brought with it a period of renewal for the line. Increased revenue allowed the railroad to modernize infrastructure, strengthen bridges, and relay much of its 125-mile main line with heavier rail. With these improvements came opportunity, the railroad expanded beyond freight, introducing commuter rail service between Santa Fe, Española, and the growing scientific community at Los Alamos.

Commuter Rail

With the line upgraded and traffic steadily increasing, the Los Alamos Northern Line Railroad recognized a new opportunity: connecting the communities of northern New Mexico more directly with Santa Fe. Commuter service was introduced, linking Española and Los Alamos with daily runs to the state capital and Albuquerque. The service was modest at first, a handful of trains timed to meet the needs of workers and students, but it quickly became an essential lifeline for the region.

The railroad’s connection to Los Alamos National Laboratory further strengthened its role. Scientists, engineers, and support staff relied on the trains for their daily commute, giving the line a unique blend of industrial and civilian purpose. Stations were upgraded with modest platforms and shelters, and schedules were coordinated to allow for maximum usage of the line.

Beyond mere transportation, the commuter service fostered economic growth along the corridor. Local businesses in Española and Los Alamos flourished, and tourism saw a quiet boost as visitors discovered the dramatic landscapes of the Jemez Mountains and the cultural richness of northern New Mexico. The Los Alamos Northern Line had transformed, no longer simply a freight route for copper and goods, but a vital thread connecting communities, industry, and the high desert itself.

The Santa Fe Southern Railway came into existence in 1992, born from the sale of the branch line by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway. For decades, it operated as a modest yet vital connection, interchanging with the BNSF Railway at Lamy while offering scenic passenger excursions along its 18-mile stretch. The line, however, faced turbulent times, particularly in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, which left it struggling to maintain independent operations.

In the 2010s, the railroad found stability under the support of Sur Rail, the parent company of the Los Alamos Northern Line Railroad. This partnership underscored the Santa Fe Southern’s role as a key link between the Los Alamos Northern Line and the broader BNSF network in Lamy. By the 2020s, while much of its day to day operations and maintenance had been absorbed into the Los Alamos Northern Line, the Santa Fe Southern retained its own identity, proudly maintaining its name, branding, timetable, and distinctive rolling stock.